Documentary

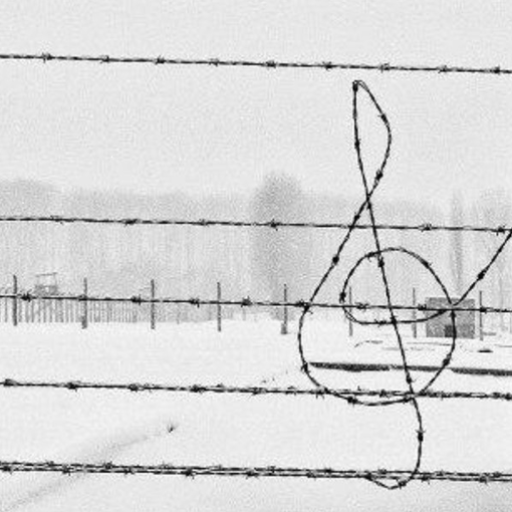

Their Music Survives highlights national and international projects bringing to contemporary audiences the works of Jewish composers and musicians who were suppressed, imprisoned, or killed during the Holocaust.

Performances

- Maestro Murry Sidlin’s Defiant Requiem concert. Sidlin’s multi-media concert-drama highlights the courageous story of composer/conductor Rafael Schächter, who used performances of Verdi’s Requiem as acts of defiance against his Nazi captors in the Terezín ghetto-labor camp. | Watch the concert

- Carnegie Hall concert: We are Here. Featuring top Broadway and TV singers, musicians, and presenters, the sold-out We are Here concert focuses on works from 14 songbooks of Holocaust-era Jewish folk songs. | Watch the film

- Maestro Gürer Aykal’s Carnegie Hall world premiere of Auschwitz survivor Michel Assael’s work, Auschwitz Symphonic Poem. The inspiring story of Auschwitz orchestra survivor Michel Assael, a Greek-Jew who composed a 1947 symphony documenting his experience. A series of incredible coincidences brought the symphony to life after it had lay never-performed in a suitcase for more than 70 years. | Read about the show

- Maestro James Conlon’s Recovered Voices performances. L.A. Opera Music Director Maestro James Conlon’s Recovered Voices performance series gives new voice to Jewish Holocaust-era composers whose works were banned and otherwise suppressed by the Nazis. | Biography | Colburn School

- Acclaimed Pianist Phillip Silver’s performances of rediscovered works. Silver has spent the past 20 years rediscovering, recording, and performing works of Jewish composers who were suppressed or killed during the Holocaust, including Leone Sinigaglia and Bernhard Sekles. | Biography

- The Violins of Hope project, including its recent 7-week run of 68 events in Pittsburgh. The Violins of Hope is a traveling international musical project featuring dozens of restored violins that once were owned and played by Jewish musicians caught up in the Holocaust. The violins have been donated by survivors, friends and family to father-and-son Israeli luthiers Amnon and Avshalom Weinstein. | Project | Biography

Production

Producer and host

Mat Edelson is a former reporter and producer for NPR’s Morning Edition. His past Holocaust-related projects include reporting on the Nuremberg Prosecutors, and the establishment of the American Red Cross’ Holocaust Victims Tracing Center. A National Magazine Award finalist for Public Service Reporting, Edelson also hosted the Johns Hopkins Radio Health Newsfeed, a daily CBS Radio medical program.

He is the author of five books published by Penguin Random House, with additional works included in Houghton-Mifflin’s Best American Sportswriting, and the Museum of Radio and Television. | Biography

Listen on these stations

- CHSR-FM (Fredericton, New Brunswick, CA)

- Georgia Public Broadcasting (19 stations across Georgia)

- KBUT (Crested Butte, CO)

- KECG (West Contra Costa, CA)

- KUHF (Houston Public Radio, TX)

- RadioStPete Florida

- Troy Public Radio (Troy, AL)

- WGBH Radio Boston

- WLRN (Miami/Ft. Lauderdale, FL)

- WRKF (Baton Rouge, LA)

- WUOT (Knoxville, TN)

He is the author of five books published by Penguin Random House, with additional works included in Houghton-Mifflin’s Best American Sportswriting, and the Museum of Radio and Television. | Biography

He is the author of five books published by Penguin Random House, with additional works included in Houghton-Mifflin’s Best American Sportswriting, and the Museum of Radio and Television. | Biography

Producer and host

Holocaust Music Education

Books

- Gilbert, Shirli. Music in the Holocaust: Confronting Life in the Nazi Ghettos and Camps. Oxford University Press, 2005

- Haas, Michael. Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned By The Nazis. Yale University Press, 2013

- Grymes, James A. Violins of Hope: Violins of the Holocaust-Instruments of Hope and Liberation in Mankind’s Darkest Hour. Harper-Perennial, 2014

- Karas, Joža. Music In Terezín: 1941-1945. Beaufort Books/Pendragon Press, 1985

- Golabek, Mona and Cohen, Lee. The Children of Willesden Lane: Beyond the Kindertransport: A Memoir of Music, Love, and Survival. Grand Central Publishing, 2002

- Koen, Renan. Positive Resistance. isbn 978-605-2061-29-9, 2021

- Laks, Szymon. Music of Another World. Northwestern University Press, 1979/1989

Organizations

Listen

Transcript

Mat Edelson (HOST): To be a Jewish composer or musician under the Third Reich’s reign of terror meant your next note could be your last. At first their works were banned as being degenerate, their contributions to the musical canon erased from public display. Later, as the murderous frenzy exploded in the ghettos and concentration camps, composers and musicians imprisoned there refused to be stilled. On scraps of paper they penciled their inspirations, praying that even if they died, their music would survive. Miraculously, it has. In this documentary, we’ll meet conductors, musicians and others rediscovering this lost generation of music and performing it for new audiences worldwide. They’re using this music to educate, to remember, and to correct an historical injustice. Join us now for Their Music Survives.

SEGMENT A

Host: Welcome to Their Music Survives. I’m your host, Mat Edelson. When one thinks of music from the Holocaust, Hollywood is often the touchstone:

(Music-Theme from Schindler’s List)

Host: That’s the theme from the Holocaust drama Schindler’s List. This haunting music resonated deeply worldwide; the score won an Oscar and a Grammy, and United Kingdom classical music fans voted Schindler’s List the most popular film soundtrack ever. Ironically, Composer John Williams initially balked at director Steven Spielberg’s offer to score the film. Williams had understandable reservations:

JOHN WILLIAMS: “How could you ever write music that is worthy of, of describing the Holocaust and the experience that people have had, something unimaginable, unthinkable.”

Host: Who could blame Williams for his reticence? In retrospect, to do musical justice to the Holocaust seems a herculean task. Yet in real time, in the 1930’s and 40’s, dozens of Jewish composers and hundreds if not thousands of Jewish musicians tried to do just that. They used music as an outlet for their culture and their humanity in the most inhumane of times.

(MUSIC-Renan Koen playing Gideon Klein’s PA 9-Allegro con fuocco)

Host: Hard as it may be to fathom, music often flourished in the ghettos and concentration camps, such as this work by Gideon Klein, who was killed in a labor camp. Some composed and played by choice, others by Nazi command under the threat of death. Of course, many played just to survive the day, but music was also an emotional outlet, a temporary artistic escape from hell, a way to express everything from sorrow to rage to resistance. In the immediate aftermath of the war, much of this music was lost, presumably forever. And yet, as we’ll explore during this hour, their music has survived, rediscovered by those who often had no idea it existed in the first place:

MURRY SIDLIN: “I stopped at a bookstore, and there’s a pile of books and I pull out a book, and I open in up and it says, ‘Music in Terezin’ and I closed the book and I said ‘Nonsense. Can’t be. Can’t be.’ First off, why would you want to, why you write music in a place like that? This is a prison for being Jewish.”

Host: That’s Washington, DC-based Maestro Murry Sidlin. The “Terezín” he’s referring to was a ghetto-labor camp, also known as Theresienstadt, where 33,000 Jews were killed and another 88,000 deported to Auschwitz and other death camps. It was that book—Music in Terezín, 1941 to 1945–by Czech Violinist Joža (YO-zha) Karas, that permanently changed the trajectory of Murry Sidlin’s life and career.

(Music from Verdi’s Requiem-Dies Irae)

Host: That’s Verdi’s Requiem, one of the most difficult pieces for a conductor to undertake, given the large choir needed to perform the work. And yet, as Murry Sidlin learned from Karas’ book, Jewish Romanian musician, composer, and conductor Rafael Schachter, who was later killed during a death march, somehow formed such a choir, and conducted 16 performances of Verdi’s Requiem in Terezín. The last of those performances, on June 23rd, 1944 was an act of pure defiance. For in the audience, for the first time, were Nazi officials. They were there to fool visiting International Red Cross inspectors into believing that Terezín was somehow a humane work camp, using the Requiem performance as an example of their benevolence. Yet the prisoner performers were having none of it. Their voices sang out a Latin condemnation of their captors:

(Music from Verdi’s Requiem-Dies Irae)

MURRY SIDLIN: “There’s one Latin sentence, ‘quidquid latet apparebit; nil inultum remanebit.’ Whatever is against God’s will will be exposed and nothing will remain unavenged. Let me say that again; Nothing will remain unavenged. They could sing what they couldn’t say.”

Host: Murry Sidlin spent years finding out everything he could about Schachter and the requiem. He even brought a choir back to Terezín for a performance of the Requiem. Sidlin’s commitment to a faithful reenactment was all-consuming. He rehearsed his 100-plus member choir in the same cramped, damp cavern that Rafael Schachter and his fellow prisoners had used for their rehearsals. That moment was captured in the documentary Defiant Requiem.

MURRY SIDLIN (Addressing His Choir Rehearsing in Terezín): “Okay, let me have your attention. This is, to me, a very religious moment. After many, many hours per day of slave labor, these people were compelled to come to this cold, dank, airless place and rehearse the Verdi Requiem. But one of the most important things we can do is to once again sing this music to these walls which heard it and absorbed it years ago and have not heard it since. All of this is to say to not only the survivors, but those who didn’t survive, that they have been heard. And we so honor them. So let’s see if we can sing through this. Give us the B-Flat again…”

(Music up…soprano singing “Requiem…Requiem…”)

Host: The documentary, which aired on PBS and is available on streaming services, reminds contemporary audiences what being able to sing the Requiem meant to the original choir members, survivors such as Zdenka Fantlova, Felix Kolmer, and Marianka May:

ZDENKA FANTLOVA: “During a performance it was not entertainment. It was a fight for life.”

FELIX KOLMER: “It was something which made us strong. It is the reason why we are calling it cultural resistance. It has given us a resistance against our fate.”

MARIANKA MAY: “We just tried to reach something that’s bigger than we. And let’s hope that we are singing to God, and God can’t help but hear us.”

Host: Murry Sidlin certainly heard them. In addition to the multitudes who’ve seen his documentary, his choir has performed the Defiant Requiem worldwide. This includes a recent sold-out 20th Anniversary show at DC’s spacious Music Center at Strathmore. The performance includes music and story, entertainment and enlightenment, soaring voices and searing prisoner testimonies. Through it all, Sidlin sees performing the Requiem as the ideal vehicle to memorably teach new generations about the Holocaust, powerfully going beyond the impact of any words he could write on the subject.

MURRY SIDLIN: “What I am is not a scholar, I am a messenger. And to be a messenger, you’ve got to have the wherewithal and the means to deliver the message. If I wrote this article, and got it into some periodical, okay, how many people over the next year or two are going to read it and see it? But in one performance, I’m gonna reach 2,400 people. In one performance. Now, we have had 52 performances.”

Host: That’s 52 times Sidlin’s brought his vision to fruition, honoring both a fellow maestro and an incredibly courageous choir:

MURRY SIDLIN: “I wanted people to know the name of Raphael Schachter, to give him something of the career he never had. And that the next time anybody hears the Verdi Requiem, they will think of it in the context of the Terezín prisoners and of the Terezín camp. That’s it. Those are the two objectives.”

(MUSIC-VIOLIN INTERLUDE TO NEXT STORY)

Host: You’re listening to Their Music Survives. I’m your host, Mat Edelson.

(Music up, from “We Are Here” concert, song “Minutn fun bitokhn”—“Moments of Certainty”—lyrics heard are,

“Only love and patience, but keep in your hand;

Our old faithful weapon, from our old native land;

Sing and dance you butchers, long we will not wait!;

Once there was a Haman, he will be your fate! Yes, he will be your fate!”)

Host: What you’re hearing is music from a sold-out Carnegie Hall concert called We are Here. The concert featured 14 Holocaust Era Jewish folk songs which ran the gamut of emotions. For as the 2900 in attendance were to learn, no two Jewish composers experienced the Holocaust in quite the same way. Those differences came out in their music. Here is We are Here’s co-Executive Producer Rabbi Charles Savenor, addressing the crowd at the beginning of the concert…

RABBI CHARLES SAVENOR (on Carnegie Hall stage addressing audience): “The truth is, the music of the Holocaust is not all sad. We will discover when life was uncertain, not every thought was about death. The beautiful music we will hear this evening is as much about love, hope, faith, and family as it is about sadness, longing, and despair.”

Host: We spoke with Rabbi Savenor, who said the genesis of the concert came several years ago, shortly after the death of author and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel. Savenor ran into an old friend, Chicago music producer Ira Antelis, on a street corner in New York City.

RABBI CHARLES SAVENOR: “And after we caught up, Ira said, ‘Who’s responsible for memory of the Holocaust after Wiesel’s passing?’ I said, Ira, that’s a very big question you’re asking. He said, ‘No, really, really, like, it’s really up to us.’

Host: Antelis told Savenor about 14 songbooks, each of which contained songs written and performed in the ghettos and concentration camps. Antelis’ dream was audacious. Not only did he want top Broadway and television talent singing the songs, he wanted to stage the show in Carnegie Hall:

RABBI CHARLES SAVENOR: “I think at that point, Ira’s wife and I agreed that he was certifiably crazy (laughs). So I said, ‘Ira, what are you talking about?’ So he said, ‘We’re going to feature a song from each of the 14 songbooks, and this music deserves to be played in the most prestigious Hall in the world.’ It was that simple. And when he put it like that, it wasn’t crazy at all. It was the most beautiful tribute that we could give to these artists.”

TRACK: Antelis and Grammy Award Winning pianist and arranger Lee Musiker, lined up the musical talent—people such as Harvey Firestein and, singing here, Tony and Grammy nominee Shoshana Bean…

(MUSIC UP-Shoshana Bean singing Main Zawoe-My Testament. Lyrics are:

“I want to see clearly,

and live to see the day;

That my brothers and sisters,

stop suffering this way…”)

Host: Meanwhile, Rabbi Savenor booked the presenters for each song. His vision was inclusive, including reaching out to German Consul General David Gill, and New York City Cardinal Timothy Dolan. At the concert, Dolan quoted Elie Wiesel, who noted that when you listen to a witness, you become a witness…

CARDINAL TIMOTHY DOLAN (ON STAGE AT CARNEGIE HALL ADDRESSING AUDIENCE) “That’s why an event like this matters to me. At a time when we soberly see anti-Semitism on the rise, is it ever important that we do all that we can to make certain that the horrors of the past never become the tragedy of today. (audience applause)”

Host: Dolan and Gill RSVP’d their acceptance to be presenters within 24 hours, but one question remained. It’s one thing to book Carnegie Hall. But filling the place? Savenor says there were doubters.

RABBI CHARLES SAVENOR “The response from three major Jewish organizations that will remain nameless is, ‘we so appreciate your vision, and agree that this is going to be wonderful. But we can’t take the risk by becoming a partner.’ The risk is, what happens if you hold a concert and nobody shows up?”

Host: Ten years ago, in calmer times, that might have been the case. But Savenor says the rise of anti-Semitism, bigotry, hate speech, and soul-crushing divisiveness has many people looking for unity and community wherever they can find it. The result was a sold-out house and an audience that left Savenor filled with gratitude.

RABBI CHARLES SAVENOR: “To look out into the audience and not just see Jews, but to see Catholics, Christians, Islamic, folks, many whom are my friends, right, but this is 2900 people at Carnegie Hall; to know where people got their tickets and to know why they came and to understand that we weren’t preaching to the choir, that the choir brought their friends, was incredibly meaningful.”

Host: The concert concept proved so successful that it was also performed in Chicago, with additional shows on the horizon. For Rabbi Savenor, these We are Here performances build on the Jewish idea of Tikkun Olam, the never-ending quest of helping to repair the world.

RABBI CHARLES SAVENOR: “The healing I think that we did was that we opened our hearts to the larger community, and the larger community open their hearts to us. With a realization that if we learned anything from history, that the real healing needs to be done by everyone, that we make memory and healing our shared responsibility because to create a situation where ‘never again’ ever happens, it’s going to take all of us, all of us.”

TRACK: You’re listening to Their Music Survives. We’ll be right back.

(END SEGMENT A)

SEGMENT B

Host: Welcome back to Their Music Survives. I’m your host, Mat Edelson.

(Music Up-Maestro Gurër Aykal instructing orchestra as they play Michel Assael’s “Auschwitz Symphonic Poem”)

Host: At Manhattan’s Dimmena Center for Classical Music, a rehearsal of a world-premier performance is taking place.

(Music Up-Maestro Gurër Aykal instructing orchestra as they play Michel Assael’s “Auschwitz Symphonic Poem”)

Host: While Turkish Maestro Gurër Aykal puts his 72-piece New Manhattan Sinfonietta orchestra through its paces, Deborah Assael sits along a wall, scanning an IPad. On it is a remarkable musical score. It was written by her father, Michel Assael. Now to Greek-Americans of a certain age, Michel Assael’s name may ring a bell, not for classical compositions, but for Greek music such as this:

(MUSIC UP-Greek folk song “To Spourgitaki”)

Host: That’s Assael’s band, Michel and Papes. They were the New York Greek community’s go-to band for just about every formal affair, so popular they booked two years out. But there was another musical side to Michel Assael, a symphony score that lay never performed in a suitcase for more than 70 years. For he, a Greek Jew, had played in an Auschwitz orchestra and somehow managed to survive. Back in Greece shortly after the war, broke and bereft, Assael tried to make sense of what he’d witnessed in the only way he knew how…through music…

(Music Up-somber string section from “Auschwitz Symphonic Poem”)

TRACK: Assael called his composition, simply and starkly, Auschwitz Symphonic Poem. On the 1947 score, done before an official death count had been finalized, Assael wrote that his work was, quote, “In memoriam of five million hostages slaughtered in the concentration camps, innocent victims of the most unhuman and barbaric frenzy.” There was another composer’s note from Michel on the score, a glimpse into his emotions that drove the piece. Daughter and Cellist Debbie Assael:

DEBBIE ASSAEL: -“So he wrote up a little preface to it, that kind of, in musical terms tells you certain things. It’s despair, disbelief, sadness, like fury, like a kind of furious kind of music…”

(MUSIC UP-Furious, crashing section from “Auschwitz Symphonic Poem.”)

DEBBIE ASSAEL: “And at the end, the liberators with the national anthems of for the for liberators, you know, the Americans, the Russians, the French, and the British superimposed on top of each other, like playing it at the same time. “

(MUSIC UP—National anthems overlayed from “Auschwitz Symphonic Poem”)

DEBBIE ASSAEL: “And the eternal hope that he could survive, and some people did survive, and they wouldn’t exterminate everybody. And that’s all in that piece.”

Host: Michel Assael never made clear whether the score was intended as catharis or performance. In the end, he used the score for passage to the United States; the New York College of Music was so impressed with his compositional skills that they offered him a scholarship. From there the score went back in his suitcase, where it might have stayed in perpetuity if not for a remarkable string of coincidences.

DR. JOE HALIO: “You know, the survivors, they were humble. They didn’t push the fact that they were survivors.”

Host: This is Dr. Joe Halio.

DR. JOE HALIO: “Michel did what he had to do. He wrote the symphony. Maybe he believed someday somebody would hear it. I don’t know, but he didn’t want to push it.”

Host: Now follow the bouncing ball here. Halio, a Long Island geriatrician, is on the board of what used to be called the Sephardic Home for the Aged in Brooklyn, New York. That facility, established just after World War II for Greek Jews fleeing Europe, was, in the 1950’s and 60s, the cultural center of the community. As a young boy, Joe Halio remembered going there to listen to the local band that was playing. That band was led by—you guessed it—Michel Assael. Thirty years later, Dr. Halio produced a series of documentaries on pre-war life in Assael’s birthplace, Salonika, Greece. He approached Assael for an interview. Assael demurred, saying he’d said everything he wanted to say in his symphony. That was news to Joe Halio:

DR. JOE HALIO: “I said, ‘Michel, you wrote a symphony?’ I said, ‘well, give me the symphony! (He said) ‘Joe, you’re a doctor. What are you going to do with a symphony? You’re not a musician!’ I said, ‘But Michel, you’re a musician, get an orchestra together.’ He said, ‘I need money.’ I said ‘Money is the least of the problems. Get an orchestra together, we’ll play the symphony. Money, I’ll get the money somewhere. (He said) ‘It’s never gonna happen.’ I tried.’ You know, Michel was famous.”

Host: Halio found some money, but he discovered something even better. In 2018, he met and briefly discussed Assael’s score with renowned Turkish Pianist Renan Koen.

(MUSIC UP-Pianist Renan Koen playing composer Pavel Haas’ work, “Al Se Fod”)

Host: That’s Koen playing the music of Czech Jew Pavel Haas, off her album “Holocaust Remembrance.” The album features works by Terezín composers such as Haas, Gideon Klein, and Victor Ullmann. None of them survived the concentration camps. Koen, of Sephardic Jewish background, has combed the world for these composer’s scores. She’s played their works at Terezín, and at a special United Nations Holocaust Remembrance concert. In that audience was Maestro Gurër Aykal, a legendary Turkish conductor.

RENAN KOEN: “And then right after the concert, he told me ‘I would like to play with you.’ I was so happy, so thrilled, so, so honored, so honored by him. And I told to Maestro Aykal that I would love to do a Holocaust concert. And he said, ‘Yes, yes. With a great pleasure.’ He told me that and also that ‘I would like to play with you in Carnegie Hall.’”

Host: Koen and the Maestro agreed on two works for the Carnegie Hall concert, including Koen’s Mozart piano tribute to Viktor Ullmann. But Koen and the Maestro still needed a third piece to fill out the program. Serendipitously, Renan Koen soon received a text message regarding Michel Assael’s symphony.

RENAN KOEN: “A year ago, I got a text message from Joe Holio one morning in Istanbul. I woke up with this text message. And he was telling me that, ‘Renan, I got it!’ Immediately, I understood what he meant. He got the score!”

DR. JOE HALIO: “I get this brown envelope in the mail, I open it up, and it’s the music score!”

Host: Joe Halio.

DR. JOE HALIO: “I almost fainted. And it’s like, I got hot. I mean, I started to sweat. It’s happening to me again now. And like, it’s like, my fingers started to tingle. And this is Michel’s score! Oh, my God. I mean…could this be true?! So I called up Debbie.”

Host: That’s Debbie Assael, Michel’s daughter, and a veteran Broadway orchestra performer in shows such as Frozen, Hamilton and Phantom. After some prodding, Debbie had sent her father’s score to Joe. Still, Joe Halio’s enthusiasm notwithstanding, Debbie knew there was a long, long road from handwritten score to inclusion in a Carnegie Hall performance. Was the score even concert worthy? Debbie ran it past an orchestrator, a musical expert who critiques whether a composer has the skills to create an outstanding work.

DEBBIE ASSAEL: “He called me right away and goes, ‘Debbie, this is a very serious, intricate, very well composed piece that’s sort of like Ricard Strauss,’ who wrote some very famous operas and orchestral music, and, you know, very hard to play. He said, ‘it’s pretty complicated.’ And I was like, wow, it’s like a real piece.”

Host: Renan Koen had a similar reaction.

RENAN KOEN: “Joe got the score. And he told me that ‘okay, I’m going to send it to you. So please review if it’s playable or not.’ I got the manuscript, I was so, so, so excited, of course. I said, ‘Joe, it’s a spectacular work. I mean, it should be played.’”

Host: From there the pieces kept falling into place; Renan shared the score with Maestro Aykal, who heartily approved. Joe Halio, who sits on the board of Nassau County’s Holocaust Memorial & Tolerance Center, helped secure their promotional and fundraising services for the Carnegie Hall performance. Just a few months later, Michel Assael’s symphonic poem was taking shape…

(MUSIC UP-Rushing violins from Auschwitz Symphonic Poem)

Host: …and for his part, Maestro Aykal was thrilled that Assael’s work was finally to be performed…

MAESTRO GURËR AYKAL: “I’m so happy that I’m helping a composer to come alive, you know, after how many years…”

Host: Debbie Assael was just as pleased. At first, her professional pragmatism suggested Carnegie Hall was too ambitious a venue to aim for, too unlikely a dream to ever be realized. But on the eve of the performance, well…

DEBBIE ASSAEL: “Thinking about it now, it’s entirely appropriate. That’s where it deserves to be played. He’s gonna have his moment.”

Host: And what a moment it was…

(Music Up-Sound of Auschwitz Symphonic Poem being played at Carnegie Hall)

Host: …for 20 plus minutes, Michel Assael’s music and Maestro Aykal’s musicians took the audience on a gripping ride, gliding effortlessly from tears to triumph. In his heart, Michel Assael dreamed of scoring films; in reality, he scored the soundtrack of his life. It was a monumental work, and as the performance concluded the audience rose to its feet and responded in kind.

(MUSIC UP-Auschwitz Symphonic Poem finale and audience applause)

Host: The next day, we caught up one last time with Debbie Assael. The location was the stage door to the Richard Rodgers theatre, where she was about to play cello in the Hamilton orchestra. Still processing the concert, she considered what she just had just heard, and why it’s so important that these musical memories live on.

DEBBIE ASSAEL: “I think this is just a totally unique account of somebody’s experience. That it takes on, like, a special type of testimony. He would have loved it: He would have loved the whole thing.”

(MUSIC UP-ORCHESTRAL INTERLUDE TO NEXT STORY)

Host: Welcome back to Their Music Survives. I’m your host, Mat Edelson. Our next two guests have dedicated their lives to discovering and playing the music of Jewish composers whose careers were disrupted or destroyed by the Holocaust. Maestro James Conlon is the musical director of the Los Angeles Opera. Called, “One of America’s foremost conductors,” by the Washington Post, Conlon is also the founder of the performance series Recovered Voices.

(MUSIC UP-Alexander Zemlinsky’s Die Seejungfrau-“The Mermaid”)

TRACK: That’s The Mermaid, by Alexander Zemlinsky, one of the Jewish composers Conlon features in his Recovered Voices performances. It’s no exaggeration to say The Mermaid changed Conlon’s life. When he first heard it played over his car radio in Germany one night 30 years ago, he was stunned. In fact, he parked his car in his driveway and refused to get out, listening spellbound until the piece concluded.

JAMES CONLON: “And a light bulb went off. It became an epiphany. It made me embark on, ‘I want to hear this again. I want to conduct this. I want to hear his other music. I want to conduct that.’ I read about Zemlinsky. Then I started becoming familiar with other names from the same period. Franz Schreker first, and then Walter Braufels and then later Viktor Ullmann, and then Erwin Schulhof.”

TRACK: Conlon learned that Zemlinsky fled Berlin and later Vienna when the Nazi’s invaded. World Class opera composer Franz Schreker had his academic appointment stripped by the Nazis, and his works banned. Same for Walter Braunfels. Viktor Ullmann died in Auschwitz. Erwin Schulhof’s works were banned, and he died of Tuberculosis in a Bavarian prison in 1942. The conclusion, says James Conlon, was inescapable.

JAMES CONLON: “How could I as a classical musician, not know all this music? There is no other explanation, that it was suppressed, along with the composers, in their own time. Which means that their moment on the stage, as Shakespeare might have referred to it, went unheeded, went suppressed, and then it’s very hard, because history is a cruel thing. It’s very hard for that moment to be regained.”

Host: Still, Conlon is making the effort. In addition to his Recovered Voices series of concerts, he co-founded the OREL Foundation. Their website is a repository of information highlighting Holocaust-era composers whose works still are not widely known.

JAMES CONLON: “So it seemed to me that something had to be done about this. Because in its way, the fact that now, almost 80 years after the end of World War Two, this is still the case means it is a form of posthumous victory for the Nazi regime. And I don’t want that to stand.”

(MUSIC UP-Walter Braunfels-Symphonic Variations on a French Children’s Song Op. 15)

Host: Conlon cites three reasons why these neglected composer’s works must be performed. Historically, he says it’s important to correct the record and recognize these composers’ contributions and influence on 20th century classical music. Artistically, Conlon says playing their compositions, including experimental works, are like reclaiming a long-denied musical inheritance for classical music fans. Then, there’s the moral reason for acknowledging these composers.

JAMES CONLON: “We cannot give these composers their lives back, we cannot change the experience that they had, often a cruel experience. But we can do the one thing that I think they would appreciate more than anything else, which is to name their names, and play their music.”

University of Maine Professor Phillip Silver feels similarly. The world-renowned pianist has spent the last 20 years scouring digital and print manuscript archives. He’s uncovering works of Jewish composers who were either suppressed or killed in the Holocaust.

PHILLIP SILVER: “I feel I’m doing something which is necessary. I feel like if I didn’t do it, it would be the equivalent of murdering these people a second time. The first time they weren’t allowed to express themselves publicly. This second time, we know what they’ve done. And if we don’t–they’re not here to express themselves–If we don’t do it, then what are we doing? We’re consigning them to oblivion.”

(MUSIC UP-Phillip Silver playing Leone Sinigaglia’s Chamber Music)

Host: Here’s Silver playing the work of Italian-Jewish composer Leone Sinigaglia. Sinigaglia died of a heart attack when the Nazis arrested him in Turin in 1944. Silver has also resurrected, played and recorded works by German-Jew Bernhard Sekles, who the Nazis fired from his job as director of Frankfurt’s top conservatory. Silver, who the Boston Globe called, quote, “an international collaborative pianist of the first rank,” says performing works by these Holocaust-era composers affects him deeply.

PHILLIP SILVER: “It, for me, carries a heavier amount of weight on me as an interpreter, as a performer. With a composer, Mozart died young, Beethoven died prematurely, Schubert died young, etc. All of these individuals suffered. But somehow, their suffering wasn’t state organized. And somehow that type of historical baggage that these composers had to overcome imposes a greater degree of necessity on me to be as honest as I can in my expression of their music.”

(MUSIC UP-Phillip Silver playing Leone Sinigaglia, Cello Sonata in G Major)

Host: Silver says to tell their story properly, he intensely researches these composers lives and interests. For example, he discovered that Leone Sinigaglia was an avid mountaineer who wrote one of the foremost books on mountain climbing. These are the kinds of personal tidbits Silver tells the audience about during a concert:

PHILLIP SILVER: “See, for me, when I program this material, I think of it as giving a face to one of the six million. The number six million doesn’t mean anything, it’s just too big. The number one, and if you know that one is attached to somebody that had a family, that did things of interest, that had a sense of humor, that was somebody you might have liked, you know, to have had a pint with you…Then it becomes something that you can relate to. And so for me, the important thing is providing that face: Through music, through narrative.”

Host: You’re listening to Their Music Survives. We’ll be back in a moment.

(END OF SEGMENT B)

SEGMENT C:

Host: October 27th, 2018 is a day no one in Pittsburgh will ever forget.

(SOUND MONTAGE:

NEWS ANCHOR: “This is an ABC News Special Report…”

SECOND NEWS ANCHOR “…there has been a shooting at a synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just moments ago…

DISPATCHER OVER POLICE RADIO: “…All city units are being sent to an active shooter….”

THIRD NEWS ANCHOR: “…This all happening at the Tree of Life Synagogue in the area of Shady and Wilkins Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill Neighborhood…”

POLICE RADIO-OFFICER ON SCENE: “…Suspect is talking about how all the Jews need to die. We’re still communicating with him…”

NEWS REPORTER: “…Eleven killed, six wounded. The deadliest anti-semitic attack in the history of the United States.”)

Host: In the days following the Tree of Life massacre, communities from across Pittsburgh joined with the Jewish community, often in song and prayer, trying to reckon with the incomprehensible. Now, some five years on, Pittsburgh once again turned to music to continue its healing and fight anti-semitism. The City of Bridges hosted 68 events over roughly 7 weeks, all centered around an international travelling project called Violins of Hope. The project featured restored violins previously owned and played by Jewish victims of the Holocaust. The instruments were mostly donated by survivors, family and their friends to the Violins of Hope collection…

(WILD SOUND UP-Single violin tuning up)

Host: At a rehearsal hall at Duquesne University’s Mary Pappert School of Music, an extraordinary scene unfolded. Eleven student violinists, some openly weeping, gazed in wonder at more than a dozen ornate Violins of Hope instruments arranged on several tables.

(SOUND UP-STUDENTS LOOKING AT VIOLINS ON TABLES)

FIRST STUDENT: “Oh, they’re just they’re lovely…”

SECOND STUDENT: “They’re beautiful…”

THIRD STUDENT: “Feeling a little overwhelmed.”

FOURTH STUDENT Well, you don’t see instruments today with the kind of attention to detail on just like genuine aesthetic.

FIFTH STUDENT: “These are so intricate.”)

Host: The students were here for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a chance to play these violins in concert.

NATHANAEL TURNER: “This violin on the back, there’s a large Star of David that’s made out of mother of pearl that is inlaid in the very center…”

Host: Duquesne violinist Nathanael Turner cradled one of the violins and marvelled at its workmanship.

NATHANAEL TURNER: “I have to say this is one of the most beautiful, beautiful things I’ve ever seen. When I picked up this one up and looked at the back, it brought a tear to my eye.”

(MUSIC UP-STUDENT MUSICIANS REHEARSING SAMUEL BARBER’S ADAGIO FOR STRINGS)

Host: And just minutes later, these instruments, which once witnessed so much death and destruction, sprang back to life, resurrected by a new generation of talented hands and open hearts…

(MUSIC UP-STUDENT MUSICIANS REHEARSING SAMUEL BARBER’S ADAGIO FOR STRINGS)

Host: After rehearsing Samuel Barber’s profound Adagio for Strings, Duquesne graduate student Michelle Kenyon was still processing the moment. Each violin came with a small card explaining its backstory; Kenyon’s violin had been played by a man who had endured a forced labor camp.

MICHELLE KENYON: “So like, hearing that story I was filled with, I was filled with sadness, I was filled with, like, hope, I was filled with anger for these people. And what they went through, and it was a lot all at once to be taking in, but to be touching something that gave someone enough hope to survive those circumstances is…I can’t put it into words.”

ANNE VICTORIA NASEVICH: “Then you’re thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, these were instruments played by people who suffered so much in concentration camps…’”

Host: Duquesne Senior violinist Anne Victoria Nasevich.

ANNE VICTORIA NASEVICH: “…and to actually touch the instruments that they have touched, it’s so memorable. And I think that we’re keeping their memory alive, the ones who died. And that’s one way of remembering, and I think Violins of Hope, the ‘hope’ part is that remembrance part.”

Host: The collection was assembled by 84-year-old Israeli Amnon Weinstein. Weinstein is a revered second-generation luthier, a maker of stringed instruments. In his small Tel Aviv workshop, Weinstein lovingly repaired and restored each donated violin to concert condition. He also learned as much as he could about the violins’ original owners.

AMNON WEINSTEIN: “This is the mission. And this is the most important part. Because I want that the instruments will stay on the stage and tell the story. And they are talking for the people that cannot talk anymore.”

Host: Each restoration, for which Amnon received no pay, took as long as 24 months. Many of the violins arrived at his shop in very poor shape. They had often been played outside in extreme weather, in ghettos and concentration camps, or in the woods where the Partisans hid. For Weinstein, the work is extremely personal; he lost 400 members of his extended family in the Holocaust. Some 30 years ago, when his collection was much smaller, Amnon was interviewed on Israeli radio. He pleaded with the listening audience to donate instruments, regardless of their condition.

AMNON WEINSTEIN: “And I told the story and asked, ‘please, if somebody has a violin, viola, a cello, a story, anything about violins and the Holocaust, please, please, please bring it to me.’”

Host: The public responded, and Amnon’s collection grew to 101 instruments. He partnered with his son Avshalom, also a luthier, to create Violins of Hope. The exhibition has travelled to Phoenix, Chicago, Cleveland, Nashville, and international venues. At the Pittsburgh Opening Night Reception, German Ambassador to the United States Andreas Michaelis emotionally recounted hearing a Violins of Hope concert. It was held in Berlin on International Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2015. That marked the then-70th Anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. The Violins of Hope instruments were played by the Berlin Philharmonic.

(MUSIC UP: Berlin Philharmonic playing Bach’s Violin Concerto in A minor: Andante)

ANDREAS MICHAELIS: “It was indeed an exceptional experience, to listen to the instruments of victims of the Holocaust in Germany on such a significant date…”

Host: Andreas Michaelis.

ANDREAS MICHAELIS: “Forgive me if this moves me, but it moved the musicians so very much that their tears were running during the concert.”

(WILD SOUND FROM POSNER CENTER EXHIBIT

DOCENT SPEAKING: “Violins were apparently something that was extremely important to a family…)

Host: The educational centerpiece of the Violins of Hope program was an exhibit of two dozen restored violins at Carnegie Mellon University’s Posner Center. The exhibit was an interactive way of learning about the Holocaust, showing how Jews kept their music and culture alive, no matter how dire the circumstances. On one tour, a docent stopped in front of a violin that had been played in a Lithuanian ghetto…

DOCENT SPEAKING TO TOUR GROUP: “Ghettos were terrible places. They were totally poverty stricken, disease stricken, all the rest of it. But they created orchestras. That’s the amazing thing. Wherever they went, they created a way to play music. And so even in ghettos, there were ghetto orchestras. And now, that is what lifted people’s spirits, I believe.”

Host: Carnegie Mellon Freshman Leo Yang took in the tour, which also showcased violins played in Auschwitz, Terezín, and other camps. Yang said while reading about the Holocaust would be impactful…

LEO YANG: “But I feel like music just connects with people on like a deeper level. And so by learning about these violins, I think we’re just connected to these stories on a more emotional level.”

Host: Pittsburgh area High School teacher Joshua Baker said his students could definitely benefit from seeing the exhibition.

JOSHUA BAKER: “If you’re in person, if it’s in the flesh, and to have something tangible, a sign that you can actually see like this (violin) that was taken and passed down, and this is an object that was real and played…Anything to bring it home, because the page is so cold, but an instrument is so real.”

Host: For Violins of Hope Pittsburgh Chair Sandy Rosen and co-Chair Pat Siger, using music and its message of resilience to teach students about the Holocaust was part of their programming goal. In addition to funding buses for Greater Pittsburgh area schools to access the Posner Center exhibit, volunteer violinists also visited schools to play and educate students. Project Manager Lynn Zelenski.

LYNN ZELENSKI: “There was a very strong initiative from the very beginning, that, if at the end of this project, we’ve left people thinking and with a little bit more kindness, then, we’ve done a good job.”

(MUSIC UP-FROM “STORIES FROM THE VIOLINS OF HOPE” CONCERT, Zog Nit Keynmol-“Never Say-Partisan Song”)

Host: For renowned cellist Aron Zelkowicz, heard here playing a famous Jewish Partisan song, Violins of Hope was a unique opportunity. The founder of the Pittsburgh Jewish Music Festival, Zelkowicz collaborated with UNC-Charlotte musicologist James Grymes, who wrote a book on Violins of Hope. The result was a riveting concert at Temple Emanuel of South Hills. The show featured stories and traditional Jewish music, with Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra violinists playing Violins of Hope instruments. The musicians and speakers were assembled on the Temple’s altar. Rabbi Mark Joel Mahler introduced one song, a lament popularized in the Warsaw Ghetto and other prisons Jews were forced to endure…

RABBI MARK JOEL MAHLER (Addressing audience): “Although it predates the Holocaust, the song became popular among Eastern European Jews, who had been forced from their jobs and their homes…They had nowhere to go. The song’s chorus asks, ‘Where shall I go? Who can answer me? Where shall I go when every door is locked? The world is large enough, but for me, it’s small and crowded. Everything I see is not for me. Every road is closed. Where shall I go?’”

(MUSIC UP-Orchestra plays Vu Ahin Zoll Ich Geyn—Where can I go?)

Host: Writer-Performer Elinor S. Nathanson told the story of Viennese-Jewish Composer Herbert Zipper. Zipper, who survived the Holocaust, created a clandestine orchestra in the Dachau concentration camp. They performed in an unfinished latrine building. 20 prisoners would shuffle in at a time for a 15-minute performance. Both the musicians and audience risked death just by being there, but it mattered not to the participants.

ELINOR S. NATHANSON: “The music served as an inspirational reminder of the humanity that Dachau had taken from them. When they listened to the music, they were no longer weak, demoralized, or humiliated. They were dignified and strong, united in their spiritual resistance to Nazi persecution. If only for 15 minutes a week, they were surrounded not by the ugliness of the concentration camp. But by the beauty of music.”

(MUSIC UP-ORCHESTRA PLAYING A WARSAW POLONAISE-I-Allegro Moderato)

Host: For Pittsburgh Symphony Violinist Jennifer Orchard, the performance held special meaning. Orchard played instrument number 97 from the collection, formerly owned by a Jewish survivor who had fled to Shanghai, China.

JENNIFER ORCHARD: “Well, you know, every instrument has a story. But these ones, you know the story, and it’s, it’s a sad story. And it’s tragic. So picking up these violins is…it’s like picking up something that’s left. And that makes you feel like to handle it with care and give it a little beauty. That’s all you can do.”

Host: Pittsburgh Symphony Harpist Gretchen Susan Van Hoesen:

GRETCHEN SUSAN VAN HOESEN: “What an amazing opportunity to connect with some unbelievable past that we have to remember. Their voices are being heard, again, now, on this concert, and it’s just pretty amazing.”

Host: What long-term impact this concert and the other Violins of Hope events had on Pittsburgh remains to be seen. Can such a musical experience help heal a wounded community? Temple Emanuel Rabbi Aaron Meyer, was optimistic:

Rabbi Aaron Meyer: “That there is something about the Jewish spirit that continues to seek beauty in this world and seek sources of culture and enlightenment and uplift, even through its most dark periods. The Pittsburgh community experienced such a dark period recently, and never lost its spirit. In many ways it brought the Jewish community closer together internally, as well as with our neighbors, and this is a natural outgrowth of allowing the community’s light to continue to shine in the world.”

(MUSIC UP-Orchestra Playing Bloch’s Prayer)

Host: Thank you for joining us for Their Music Survives. For more information on this documentary, go to theirmusicsurvives.org. I’m your host, Mat Edelson.

(MUSIC FADES)

(End Segment C)

(End Show)